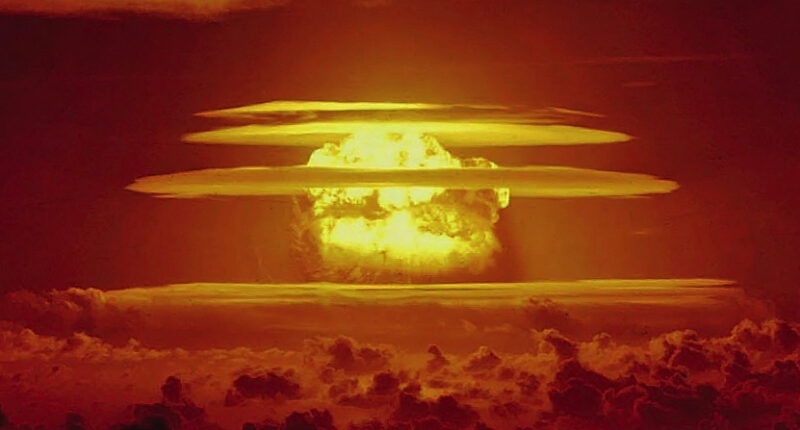

A team of Chinese army scientists ran a laboratory simulation to answer a stark question: what happens if three nuclear warheads hit the same spot in quick succession?

Led by Xu Xiaohui, an associate professor in Nanjing, the group modelled the test on the US Palanquin experiment from 1965, triggering a single 4.3-kiloton equivalent blast at about 85 meters (279 feet) deep.

Compared with the Palanquin baseline, the triple-strike setup more than doubled the crater radius, from 46 meters (151 feet) to 114 meters (374 feet), and increased depth from 28 meters (92 feet) to 35 meters (115 feet).

Xu’s team did not disclose total damage figures, but said staging the detonation into three pulses produced a crater roughly ten times larger in volume than a single equivalent blast.

A smaller run — a 5-kiloton pulse at 20 meters (66 feet) deep — still produced a much larger surface damage area than Palanquin, from about 6,600 square meters (71,000 square feet) to 26,400 square meters (284,000 square feet).

“This study shows … that deeply buried multi-point explosive sources exhibit significantly higher cratering efficiency than single-point sources, providing data support for coordinated multi-warhead penetration strategies using nuclear earth-penetrating weapons,” Xu’s team stated, as quoted by South China Morning Post.

Behind the Test

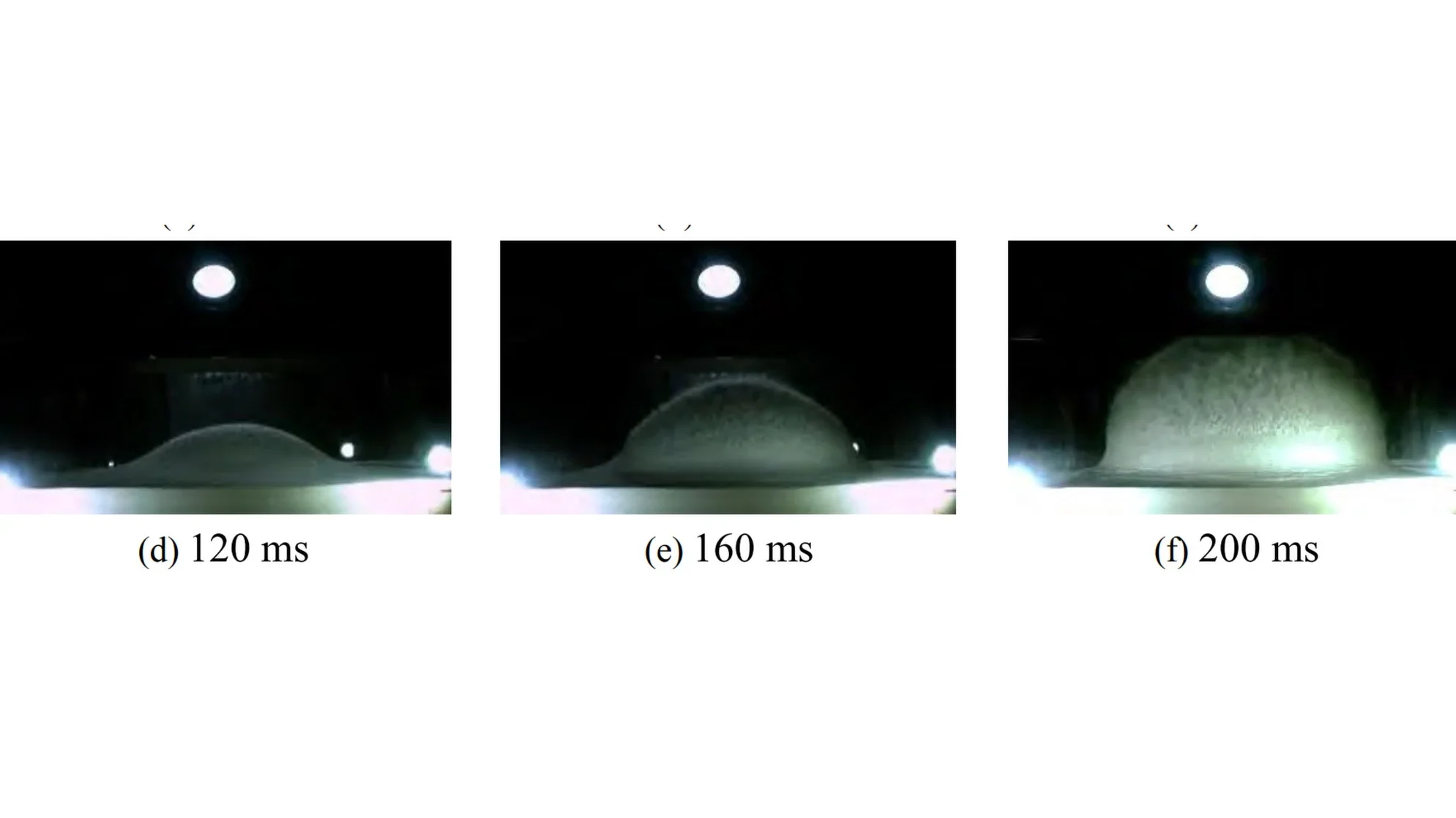

To avoid real nuclear detonations, Xu’s group used a vacuum-chamber rig that reproduces the rapid pressure pulses of a high-yield nuclear blast at small scale and far lower cost.

A two-stage gas gun smashed pressurized glass spheres with projectiles to release controlled gas pulses, a setup that mimics the quick energy release of a nuclear explosion in a way the researchers can repeat and tune.

With blasts spaced about 0.8-millisecond apart, the pulses merged into what the researchers describe as a single, amplified blast rather than scattered shocks.

Military Implications

Replicating these effects on an actual battlefield would require multiple highly precise warheads with advanced features such as hypersonic delivery and pinpoint guidance.

Military forces would also need sophisticated command-and-control systems to synchronize timing and targeting across munitions.

According to the research team, these capabilities are more attributed to modern nuclear warheads than traditional ones.

Xu’s group at the Army Engineering University of the People’s Liberation Army said the test could “directly serve [China’s] security and protection needs for deep underground engineering.”